Great businesses are built by great leaders—not prophets (part 2 of 3)

In an earlier posting, I reviewed whether mental illness was a pre-requisite for great leadership, and concluded that this was not the case. However, occasionally these far-reaching perspectives do match reality and, assuming the requisite knowledge, intellectual capacity and motivation are also in place, then the triumph of these problem-solvers can be spectacular; Winston Churchill provides but one example.

But whilst excelling in a crisis is worthy and admirable, is it the definition of great leadership? I would argue not.

Surely great leadership is about resolving big problems from a wide array of domains, and doing so for the benefit of a broad population. In my view, it is scope and scale not speciality that defines greatness.

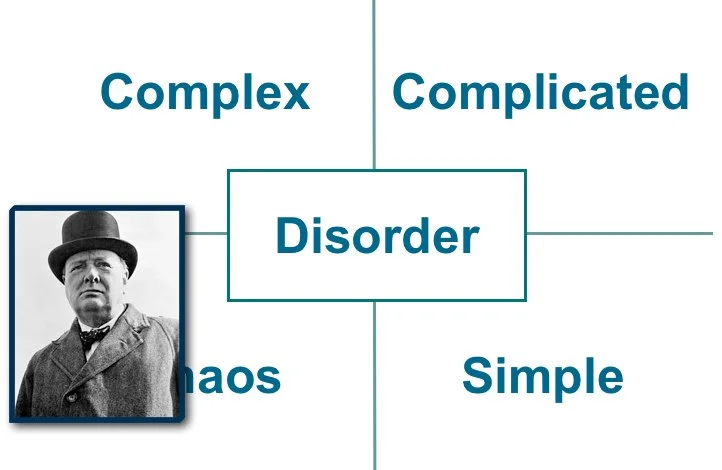

With reference to the Cynefin framework, I would suggest that an individual who excels in one problem domain is a good leader. A great leader is one who is able to solve problems across all domains with the greatest mutual benefit to all of those involved.

Good leaders excel when the problem domain and their preferred problem-solving style resonate. In this situation they come across as comfortable, relaxed, and high-performing. They appear to be at the top of their game.

For example, Operations Managers tell me they spend most their working day solving problems in the Complicated and Simple Domains. This population is comfortable with structure and processes, and has a strong disposition to solve known or knowable problem. But cracks start to show when problems arise whose solutions are unpredictable or unknowable. In these situations, expertise or precedence can provide only the most general of guideposts. Adhering too tightly to lessons from history builds misplaced confidence and leads to poor decisions. In these circumstances, the better leaders recognise the limits of their expertise and work with others better suited to that problem.

Good leaders are able to respond to their environment and adjust their behaviours accordingly. As a result they develop and improve. They grow toward greatness.

When leaders encounter chaos, they act to stabilise the situation, try to make sense of the disruption and respond rapidly and decisively. The leaders exert command and control, but recognise that chaos is transitory, and try to move from this state to more stable domains as quickly as possible.

Some, such as Churchill, thrive in Chaos. They have a dominant view of the problem and how it should be resolved. They are able to act rapidly and decisively, and when they do so successfully, the results can be spectacular. They make the front page and case studies are written on ‘the “Churchill” Way.’ Some become revered.

But their success has a potential dark side. Recognising that their power and profile will diminish as the Problem transitions from Chaos to the other domains, some leaders will maintain the chaotic state. They will manage the environment so that they always excel. I call these types of leaders, “Prophets.”

Prophets thrive in chaos. They promise stability. They give confident proclamation to an eager audience about their ability to give safety, security and predicability. But this is illusionary. Their prescriptive vision is often flawed but is clouded by the chaos. Transition out of Chaos to other domains would unmask the flaws so for Prophets extended residency in chaos is necessary for maintenance of power. In democracies, enlightened voters remove their Prophets when the job is done. Churchill tried to maintain a sense of chaos (”(Labour) would have to fall back on some form of Gestapo, no doubt very humanely directed in the first instance”) but this did not prevent his exit in a landslide Labour victory in July 1945.

Great leaders are able to engage others in resolving problems from all domains. They neither overly-focus on their disposition, nor do they deliberately maintain a transitionary Chaotic or Disorder state in order to maintain a corporate dependency.

Great leadership can be learnt. It requires a framework and experience to identify the context of the issues to be resolved. It also requires access to a wide range of networked problem-solving diversity, maintained at a low cost when not required. Finally, it requires motivation to move to areas outside of one’s pre-disposition in order to really drive up business performance. But all of this is attainable.

Where are you, and where do you wish to be?

- Prophets seek and receive their oxygen in Chaos.

- Good leaders excel in limited domains and principally rely on their expertise.

- Great leaders excel in all domains, but rely on the support of others to do so and for clear mutual benefit.

In the final part of this series, we review how Steve Jobs when from Prophet to Great Leader