Spot talent with just two questions

If you’ve been a team leader you’ve endured it; the ‘pay and performance’ meetings where bonuses and personal assessments are stuffed under the curve of a normal distribution.

Like squeezing 34” waist into slightly elasticated 30” trousers, the job will be done. And while the shape may look acceptable in the eyes of beholders, everyone in the room knows what lies beneath.

All leaders know the distribution of talented high performers is not Gaussian but Pareto. For every one Yehudi Menuhin violin virtuoso there are many, many string scratchers. An organisation would be better served to invest in making their second-best tier perform more closely to their tier 1 crew.

But this rarely happens.

So why do we try to improve the average instead of focussing on the exceptional? Instead we should be focussing our development and reward resources on the 20% (or less) that make 80% (or more) of the difference.

And what about the bulk of the population?

Let me be clear. I am not advocating a GE-style “rank and yank” approach of culling the employee population.

Like Richard Branson, I hold the view that both employer and employee have failed if someone is let go.

But I do believe individuals should take accountability for the performance improvement but there is a change of perspective required if this is to be realised.

We need to go beyond our obsession of leadership by personality. We need to focus on the process of leadership. This opens the door for individuals to become leaders of themselves or others—based of their strengths.

At its simplest, the process of leadership requires that leaders:

1. Identify the problem to be solved

2. Recruit the physical and emotional resources (i.e. People) to solve the problem

3. Solve the problem while delivering mutual benefit (rational and emotional) to all involved.

If individuals are able to apply this process in a context which matches their knowledge, motivation and ways to working, a dramatic increase in performance is achieved.

When context and capability match, only then you can start to measure leadership potential.

How can you assess leadership potential?

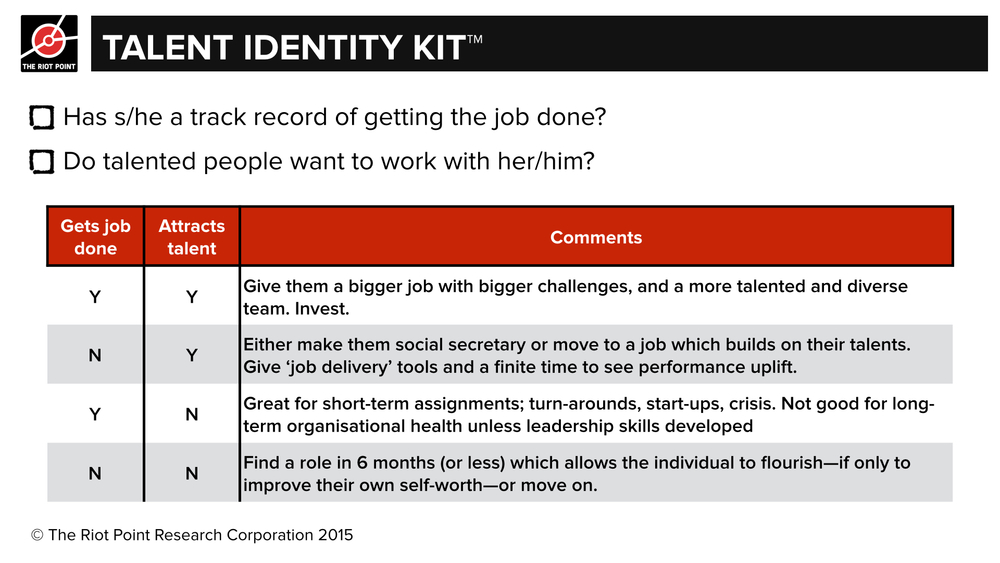

I use two heuristics, two questions, to seek out those who are successful leaders.

- Does s/he get the job done?

- Do the most talented workers in the organisation want to work for her/him?

These questions address whether problems are solved or business objectives achieved, and whether the leader is completing them while concomitantly improving the capabilities and well-being of those he is leading.

Whilst I don’t claim these heuristics to be Universal, I have found them to be useful aids to decision-making in a wide variety for circumstances. These have ranged from

- Selecting ‘high potential’ talent

- Recruitment

- Task allocation

- Deciding which colleagues to work with or (more refreshingly) not work with.

I have also found this approach to be more equitable and transparent when allocating ‘pay and performance’ funds. If a leader has overtly improved a sub-ordinate’s life, there is considerably less resentment when that leader receives financial reward.

Of course there are times when a leader neither accomplishes their goals nor works with others for mutual benefit. The historical response is attempt development or remediate. The employer assumes the burden.

With this perspective the employee takes primary responsibility for finding contexts which plays to their strength. The employer provides the opportunity and support, but the employee is ultimately responsible for performance improvement. By choosing the context based on their strengths, the employee stacks the cards in his favour.

This is a good thing.

The online Problem-Solving Leadership programmes focus on becoming a better leader of others at lower personal stress